This post is part of a short series of tutorials for people who are new to using their Raspberry Pi. It will make more sense if you start at the beginning.

Continued from here.

First page here

12. Some other useful bits and bobs

Firstly, let me say that Linux is a huge subject and I’m only scratching the surface here. Also, my knowledge on the subject is not that great; I know enough to get by and Google for everything else. Secondly, all this huge operating system is contained within the 2GB SD card plugged into your Pi. That’s about £30 of hardware to create what used to be called a mainframe computer, and if you aren’t impressed by that, you haven’t understood how much your Pi can do. Here are some bits and bobs that you might find useful as you learn more.

12.1Â Pipe to your grep

Pipes were briefly mentioned earlier, as a way to stop text whooshing off the top of your screen by appending |more to the end of a command. Here is a brief, incomplete and misleading explanation of how they work.

It’s in the nature of computers that programs take something in, do something and then put something out. A program with no inputs or outputs doesn’t do much, after all. You might think that command line programs take their data in from the keyboard and put it out to the screen but they actually talk to the streams, stdin and stdout – which you can think of as being like a plug and socket, one at each end of the program, through which data is poured. It is the shell (Raspbian uses “bash” by default) that acts as an interface between you and the computer, linking the keyboard to the stdin stream and the screen to the stdout stream. Thanks to the standardised way data is pumped in and out of programs, you can join them together so the output of one program becomes the input of another. This is done with a “pipe” – | which is simply placed between the programs so that the data flows from left to right. Examples will probably make more sense than words.

“grep” is a program which searches for words through whatever text is put into it. There are many ways to use it; like searching through files for a word – let’s find lines containing the word “transmission” in the log file for dpkg (which is used by Apt):

naich@raspberrypi ~ $ grep transmission /var/log/dpkg.log

2012-08-06 12:39:49 install transmission-common:all <none> 2.52-3

2012-08-06 12:39:49 status half-installed transmission-common:all 2.52-3

2012-08-06 12:39:49 status half-installed transmission-common:all 2.52-3

... and so on ...

grep can also take its input from stdin (it automatically does this if you leave the filename off the end of the command), with a pipe. In this example, “cat filename” prints the contents of the file “filename” which is then piped to grep which prints lines containing “transmission”:

naich@raspberrypi ~ $ cat /var/log/dpkg.log | grep transmission

2012-08-06 12:39:49 install transmission-common:all <none> 2.52-3

2012-08-06 12:39:49 status half-installed transmission-common:all 2.52-3

2012-08-06 12:39:49 status half-installed transmission-common:all 2.52-3

... the same stuff as above ...

But it’s still whooshing off the screen, so let’s take the output of “grep” and pipe it to “more” (no filename after the “more” command makes it read from stdin), which paginates it:

naich@raspberrypi ~ $ cat /var/log/dpkg.log | grep transmission | more

2012-08-06 12:39:49 install transmission-common:all <none> 2.52-3

2012-08-06 12:39:49 status half-installed transmission-common:all 2.52-3

...

2012-08-06 12:40:01 status unpacked transmission-daemon:armhf 2.52-3

--More--

Or we could use “wc” to count the number of times it appears. As with “grep” and “more”, leaving off a filename makes wc read text from stdin rather than a file. “wc -l” counts the number of lines stuffed into its stdin:

naich@raspberrypi ~ $ cat /var/log/dpkg.log | grep transmission | wc -l

31

naich@raspberrypi ~ $

All these programs have man page help, by the way. grep is probably the most useful tool in the Linux toolbox so it’s worth finding out about it. Also read up about redirection, which is a related subject.

12.2Â Processes, and how to kill them

All programs that run on the Pi (known as “processes”) – autonomous daemons, interactive programs and even the program that boots it, have two things – a unique ID number (process ID or “pid”) and a user who owns it (user ID or “uid”). Well, obviously they have more than two things, but these two are the most important.

The pid is a unique number between 1 and 32768. Each process gets a pid when it starts which is one more than the previous one assigned, unless it’s already taken, in which case the next higher one is assigned. The numbers wrap round to 2 (1 is always used by the “init” process) when they hit 32768.

The process also has a user ID (uid), the same as one of the users on the system, as if the user had started the process himself. The process inherits the identity of the user, writing files in his name for example, and has the same permissions to read, write and execute files as that user. So a process running as “root”, with a uid of 0 can do anything. Processes that don’t need to run as root tend to run as their own user, in order to sand box them into their own little world. You can see this, for example with Transmission, which runs under the uid of 106 – debian-transmission.

You can get a list of processes currently running on your Pi with the “ps” command:

naich@raspberrypi ~ $ ps -ef

UIDÂ Â Â Â Â Â Â PIDÂ PPIDÂ C STIME TTYÂ Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â TIME CMD

root        1    0 0 Aug20 ?       00:00:14 init [2]

root        2    0 0 Aug20 ?       00:00:00 [kthreadd]

root        3    2 0 Aug20 ?       00:00:09 [ksoftirqd/0]

... lots of processes ...

106      2382    1 0 Aug21 ?       00:22:56 /usr/bin/transmission-daemon --c

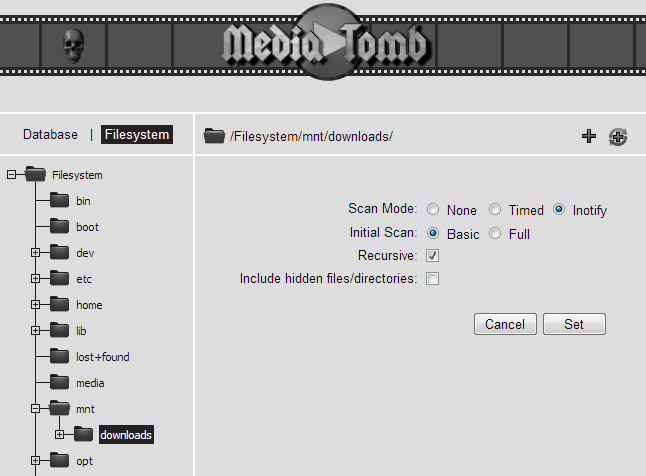

107      3527    1 0 Aug23 ?       00:13:52 /usr/bin/mediatomb -c /etc/media

root     3860 1949 0 11:35 ?       00:00:00 sshd: naich [priv]

naich    3867 3860 0 11:35 ?       00:00:00 sshd: naich@pts/0

naich    3868 3867 0 11:35 pts/0   00:00:01 -bash

naich    3941 3868 0 12:27 pts/0   00:00:00 ps -ef

naich@raspberrypi ~ $

This shows the user ID (UID), process ID (PID) the process ID of the process which started it (PPID), the start time (STIME), the amount of CPU time it has taken up (TIME) and the command that started it (CMD). Another, more interactive way to show processes is with the “top” command:

naich@raspberrypi ~ $ top

top - 12:41:13 up 3 days, 16:25, 1 user, load average: 0.00, 0.01, 0.05

Tasks: 57 total,  1 running, 56 sleeping,  0 stopped,  0 zombie

%Cpu(s): 1.3 us, 1.6 sy, 0.0 ni, 95.4 id, 0.0 wa, 0.0 hi, 1.6 si, 0.0 st

KiB Mem:   220592 total,  209612 used,   10980 free,    7192 buffers

KiB Swap:  102396 total,     568 used,  101828 free,  163588 cached

PID USER     PR NI VIRT RES SHR S %CPU %MEM   TIME+ COMMAND

2382 debian-t 20  0 43732 11m 896 S  1.0 5.1 23:02.69 transmission-da

3945 naich    20  0 4616 1348 1028 R  1.0 0.6  0:00.22 top

3527 mediatom 20  0 152m 9.9m 800 S  0.3 4.6 13:53.06 mediatomb

3867 naich    20  0 10524 1768 1056 S  0.3 0.8  0:01.54 sshd

... and so on ...

The “%CPU” and “%MEM” show the amount of CPU time and system memory each process is using at this moment and is useful in catching processes that are running out of control. Press “H” to see the help page or “Q” to quit. If you need to stop a process running and can’t find a way to do it nicely (with “service process stop”, for example), then you can kill it with kill. Let’s make a process and kill it.

naich@raspberrypi ~ $ sleep 600 &

[1] 3984

naich@raspberrypi ~ $ ps -fu naich

UIDÂ Â Â Â Â Â Â PIDÂ PPIDÂ C STIME TTYÂ Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â TIME CMD

naich    3867 3860 0 11:35 ?       00:00:01 sshd: naich@pts/0

naich    3868 3867 0 11:35 pts/0   00:00:01 -bash

naich    3984 3868 0 12:47 pts/0   00:00:00 sleep 600

naich    3986 3868 0 12:47 pts/0   00:00:00 ps -fu naich

“sleep” is a program that does nothing for the number of seconds you tell it. The “&” at the end means run it in the background, like a daemon, rather than interactively. Here you tell it to do nothing for 10 minutes and then then you get a list of the processes you are running. See the one with PID 3984 (your pid will be different)? That’s the sleeping one we are going to creep up on and kill. Brutal.

naich@raspberrypi ~ $ kill 3984

[1]+ Terminated             sleep 600

naich@raspberrypi ~ $ ps -fu naich

UIDÂ Â Â Â Â Â Â PIDÂ PPIDÂ C STIME TTYÂ Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â TIME CMD

naich    3867 3860 0 11:35 ?       00:00:01 sshd: naich@pts/0

naich    3868 3867 0 11:35 pts/0   00:00:02 -bash

naich    3985 3868 0 12:51 pts/0   00:00:00 ps -fu naich

naich@raspberrypi ~ $

RIP 3984. Poor thing never knew what hit it. If you are killing it because it has locked up, then you might need to use a bit more force. If politely asking it to die with kill doesn’t work, use kill -9 to guarantee you’ll finish it off.

12.3Â Symbolic links

Symbolic links allow more than one filename to point to the same file or directory. Similar to (and naturally predating) the Windows “shortcut”, they allow you to use a filename to point to another file or directory in a different place. They come in two types – hard links and soft links. A hard link creates a filename that refers to the physical location of the data. It will appear as a normal file but shares the same data as the file it is linked to. The more common type is a soft link, which appears as “linkname -> original_file” in long listings. Example:

naich@raspberrypi ~ $ mkdir wibble

naich@raspberrypi ~ $ echo hello >wibble/linktest.txt

naich@raspberrypi ~ $ ln -s wibble/linktest.txt softlink

naich@raspberrypi ~ $ ls -l

total 4

lrwxrwxrwx 1 naich naich  19 Aug 24 14:22 softlink -> wibble/linktest.txt

drwxr-xr-x 2 naich naich 4096 Aug 24 14:21 wibble

naich@raspberrypi ~ $ cat softlink

hello

naich@raspberrypi ~ $ rm softlink

naich@raspberrypi ~ $ ls -l wibble/

total 4

-rw-r--r-- 1 naich naich 6 Aug 24 14:21 linktest.txt

naich@raspberrypi ~ $

First we make a directory called “wibble”, then create a file in it (linktest.txt) with some text in it. ln -s wibble/linktest.txt softlink creates a soft link to “wibble/linktest.txt” called “softlink”. We demonstrate that “softlink” can be used as a real file by outputting the contents with cat softlink. Then we remove the softlink with rm softlink and show that the original file remains.

Softlinks to directories can cause all sorts of hilarious confusion if you get a bit lost:

naich@raspberrypi ~ $ ln -s / subdirectory

naich@raspberrypi ~ $ cd subdirectory/home/naich/subdirectory/home/naich

naich@raspberrypi ~/subdirectory/home/naich/subdirectory/home/naich $ pwd

/home/naich/subdirectory/home/naich/subdirectory/home/naich

naich@raspberrypi ~/subdirectory/home/naich/subdirectory/home/naich $

Eek!

12.4 Everything else

Some other other useful things to know about.

There is no on switch or reset button on the Pi, so we use the “shutdown” command to reboot or halt. Options are “-r” to reboot or “-h” to halt before turning it off. You also specify a time to do it at, or “now” to do it immediately.

naich@raspberrypi ~ $ sudo shutdown -r now

Broadcast message from root@raspberrypi (pts/1) (Fri Aug 24 14:02:39 2012):

The system is going down for reboot NOW!

naich@raspberrypi ~ $

You can also use the commands halt to halt and reboot to wipe the SD card clean. Nah, just kidding. It reboots the Pi.

For file manipulation (stop sniggering at the back), the commands are mv (move), cp (copy), rm (remove), mkdir (make directory), rmdir (remove directory). This page explains them in english.

Get information about the filesystem with the commands df and du. df shows how full the filesystems are:

naich@raspberrypi ~ $ df -h

Filesystem     Size Used Avail Use% Mounted on

rootfs         3.6G 1.4G 2.1G 41% /

/dev/root      3.6G 1.4G 2.1G 41% /

tmpfs           22M 208K  22M  1% /run

tmpfs          5.0M    0 5.0M  0% /run/lock

tmpfs           44M    0  44M  0% /tmp

tmpfs           10M    0  10M  0% /dev

tmpfs           44M    0  44M  0% /run/shm

/dev/mmcblk0p1Â Â 56MÂ Â 34MÂ Â 23MÂ 61% /boot

/dev/sda1Â Â Â Â Â Â 7.5GÂ 2.0GÂ 5.6GÂ 27% /mnt/downloads

du shows the amount of hard disk space used in a directory and all those under it:

naich@raspberrypi ~ $ du -h /etc

132KÂ Â Â /etc/console-setup

8.0KÂ Â Â /etc/rc4.d

8.0KÂ Â Â /etc/dpkg/origins

... and on and on ...

24KÂ Â Â Â /etc/gconf

3.8MÂ Â Â /etc

naich@raspberrypi ~ $

Finally, for the moment, check out uptime. This shows how long it has been since the last reboot. This is the geek equivalent of comparing penis size, so make sure you have at least a month’s worth of uptime before even mentioning it to anyone, let alone bragging about it.

naich@raspberrypi ~ $ uptime

15:24:09 up 1:21, 2 users, load average: 0.00, 0.01, 0.05

naich@raspberrypi ~ $

Yeah, an hour and 21 minutes is not going to impress the ladies. In my defense, I did have to reboot to get a screenshot earlier. And it’s very cold in here.

12.4Â Further reading

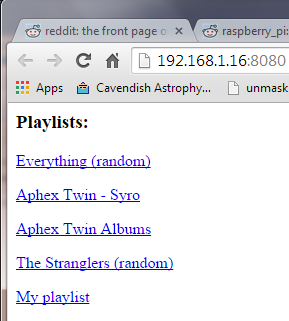

If you liked the previous Pi-rate Radio Jukebox (and 15 people did!), you won’t want to miss this latest version of it. It’s basically the same thing, but it runs as a daemon, so you can fire up your favourite tunes using a browser rather than logging in to your Pi to start up scripts. As usual it’s horribly coded in Bash and features a fuck-ugly interface with no aesthetic considerations whatsoever. You can insert prettiness yourself if you want to – it’s easy enough because the web pages are done as templates. All the code is commented to

If you liked the previous Pi-rate Radio Jukebox (and 15 people did!), you won’t want to miss this latest version of it. It’s basically the same thing, but it runs as a daemon, so you can fire up your favourite tunes using a browser rather than logging in to your Pi to start up scripts. As usual it’s horribly coded in Bash and features a fuck-ugly interface with no aesthetic considerations whatsoever. You can insert prettiness yourself if you want to – it’s easy enough because the web pages are done as templates. All the code is commented to

Note:

Note:

Notice a few things here – the “$” has changed to “‘#” to indicate you are now root, the “~” has changed to “/home/your_name because it is no longer your home directory and you are now “root@raspberrypi”. You now have absolute power over the entire operating system. Let it go to your head for a while, cackle like

Notice a few things here – the “$” has changed to “‘#” to indicate you are now root, the “~” has changed to “/home/your_name because it is no longer your home directory and you are now “root@raspberrypi”. You now have absolute power over the entire operating system. Let it go to your head for a while, cackle like